STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN was a little $450,000 movie that The Samuel Goldwyn Company released on 5 screens over Memorial Day weekend, 1991. Some time after that it expanded up to 75 screens, and it made $2.7 million dollars on that small budget. Roger Ebert reviewed it on June 28th (he liked it).

STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN was a little $450,000 movie that The Samuel Goldwyn Company released on 5 screens over Memorial Day weekend, 1991. Some time after that it expanded up to 75 screens, and it made $2.7 million dollars on that small budget. Roger Ebert reviewed it on June 28th (he liked it).

You will not not notice how low that budget is. At its slickest, STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN seems like an early ‘80s TV movie, as the saccharine orchestral score by Harold Wheeler (arranger and producer, Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk by Meco) plays over dark, grainy establishing shots of New York City buildings.

At its cheesiest it looks like a filmed community college play, with straight-on shots of family drama at a dinner table or a man looking in a mirror giving a long monologue to a white man he argued with at the gas station earlier.

At its best, though, it’s a time capsule of the Red Hook housing projects, where the director grew up, and of an exciting young actor giving a great first performance, even if he’s saying pretty on-the-nose stuff about The American Dream and shit as he points accusingly to the Manhattan skyline.

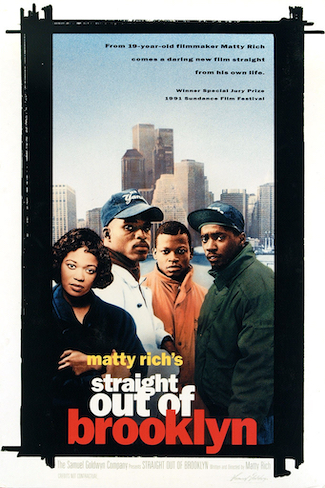

The rawness of the movie is both its strength and its weakness, and is explained by the fact that its writer/director/producer/co-star Matty Rich started writing it at 17 and was only 19 when it premiered. Predictably that gives it a certain authority about what it feels like to be a teenager in that time and place, but also a crude approach to filmmaking and drama and a young man’s guesses about adult life.

Newcomer Larry Gilliard Jr. stars as Dennis Brown, a teenager introduced fuming in the bedroom he shares with younger sister Carolyn (Barbara Sanon, no other acting credits) as they listen to their drunk dad Ray (George T. Odom) yell at and beat up their mother Frankie (Ann D. Sanders, RAISING THE HEIGHTS). Ray seems to break all the dishes in the house, then demands the kids clean up his mess before he gets home. As they do, Dennis yells at his poor sister about how sick he is of all this. So she gets it twice.

Newcomer Larry Gilliard Jr. stars as Dennis Brown, a teenager introduced fuming in the bedroom he shares with younger sister Carolyn (Barbara Sanon, no other acting credits) as they listen to their drunk dad Ray (George T. Odom) yell at and beat up their mother Frankie (Ann D. Sanders, RAISING THE HEIGHTS). Ray seems to break all the dishes in the house, then demands the kids clean up his mess before he gets home. As they do, Dennis yells at his poor sister about how sick he is of all this. So she gets it twice.

Dennis is still burning about it when he goes to hang out with his more happy-go-lucky friends Kevin (Mark Malone, “Bartender,” HERE’S TO LIFE!) and Larry (Rich himself). Larry is pretty funny, and at one point calls himself “Larry Love, Super Lover Undercover.” I think Rich also deserves a little credit for not wanting to play the lead.

I don’t think it ever occurred to me before that though the title is obviously a reference to the classic album Straight Outta Compton, it’s not the same usage at all. N.W.A are bragging about having come from Compton, while “straight out of Brooklyn” when Dennis says it refers to wanting to get the hell away from the place where he grew up.

That’s his goal when he convinces his friends to help him rob a drug dealer. For as long as it’s drawn out, it’s an unusually straightforward movie crime: go get a gun from a guy, drive past a guy and steal his briefcase, move somewhere with his girlfriend Shirley (Reana E. Drummond, no other credits). He doesn’t get to that last step.

I doubt this is the intent, but I kind of like the simplicity of it – it makes it seem more like just some guys you would know than normal movie criminals. And I think the fact that the production can’t afford costumes or anything gives it a sense of reality – people just wearing normal winter coats, not anything flashy. I’m not sure what I think about the Raggedy Ann and Andy sheets draped over two of the dining room chairs, though. Is that a thing? It didn’t seem to me like something the Browns would do.

I enjoy the period slang like “doin’ the nasty” and “bozak” and that a brick phone is used as a status symbol. And I think I would like some of the soundtrack (there’s a song by Daddy-O from Stetsasonic and another one with Daddy-O and Queen Latifah) if I knew when it even played in the movie.

I think it works better with the youthful things, especially the silly stuff (Kevin and Larry almost getting beat up by a guy wearing beads and an Africa medallion for “scheming on” his girl by talking about her “stoopid butt”) than in the scenes about Dennis’s parents. It kind of seems to me like the movie approves of Mrs. Brown defending her husband’s abuse to her daughter and repeatedly insisting that “we gotta stand by him.” And Rich kind of sounded like he still felt that way in a 2017 interview with Blackfilm in which he said, “I wanted to show a family dynamic even with all of that chaos and pain that there was a love that his father had with a wife. Even though she was abused, she stayed within that family because she knew that there was some good in that man before the pain.”

Or maybe because he’s made her too scared to leave him? I don’t agree with Rich if he’s saying that’s a good reason to stay together, but I do think it’s some of the more interesting characterization in the movie. Ray is introduced at his most abusive, and Dennis’ arc is largely fueled by his anger about it. But then kinda late in the game there’s a humanizing scene where Ray is actually nice to his son, asks him how he’s doing, and tells him a story about his youth. Dennis is even able to laugh with him. In another scene Ray is drunkenly dancing to a record when Frankie comes home, and even though she’s just lost her job because of the bruises he put on her (which is some fucked up employer shit obviously) she’s able to dance with him for a bit and smile. If these scenes were meant to balance out or justify Ray’s constant abuse I certainly don’t like that, but I think there is truth to them – that even shitty people have good qualities or moments in them.

One scene with a weird ambiguity to it is when Ray gets into a fight with a customer (Billy R., no other credits) at the gas station where he works. It’s a condescending white guy with a tie who you immediately hate, and he complains to the manger (Joseph Pillonia, no other credits) who proceeds to make racist comments about Ray to the customer. So Ray absolutely should not put up with this shit, but also he started the whole thing by just sitting in the parking lot staring into space and then telling the customer off when he asked for help. I honestly didn’t understand at first that Ray did work there, I thought he was just sitting on the curb. So if his boss wasn’t a racist dick you’d have to sympathize with his situation.

Also when Dennis said they needed money to get out of Brooklyn Larry suggested getting jobs at his uncle’s gas station, so it’s weird that there’s another unrelated gas station job in the movie.

In Roger Ebert’s three star review he said he almost didn’t mention Rich’s age up front because he felt it would be condescending. Unfortunately I think you really have to think, “Well, a kid made this” to accept some of the clumsy melodrama like Frankie freaking out over an offscreen gun sound effect or especially the ending in which which Ray, having knocked Frankie over to the point that she’s hospitalized with unspecified injuries, apologizes to everyone and promises to stop drinking and be good. Then he goes outside and is shot by the drug dealers Dennis robbed at the exact moment that Frankie dies of Padme Amidala syndrome. It ends with an onscreen moral that “WE NEED TO CHANGE,” which seems to predict the much more skillful heavy-handedness of John Singleton’s BOYZ N THE HOOD (released the next month).

This is definitely a corny movie, with filmatism sometimes reminiscent of a Cynthia Rothrock movie or if CLERKS was in color. It’s definitely more of an interesting novelty than a good film, but I don’t really have a problem with that. I think the end of Ebert’s review might be a little too charitable, but I like what he says: “The edges are rough and the ending is simply a slogan printed on the screen. But the truth is there, and echoes after the film is over.”

I remember a very big deal being made of Rich at the time – that he was a teenager, that he made the movie on credit cards and donations, and of course it was unusual that he was Black and giving his perspective of life in the projects. His movie won Best First Feature at the Independent Spirit Awards – beating Wendell B. Harris Jr.’s CHAMELEON STREET, Todd Haynes’ POISON, Michael Tolkin’s THE RAPTURE and Richard Linklater’s SLACKER. It’s an award that had also gone to SHE’S GOTTA HAVE IT. (And DIRTY DANCING.)

But honestly a more lasting honor is being name-dropped in the Ice Cube song “Who Got the Camera?” from the 1992 classic The Predator. In a story about police brutality post-Rodney King, Cube talks about being pulled over and “looking for John, Matty or Spike Lee.” So at least for the duration of that particular lyric, Rich was put on the same pedestal as circa MALCOLM X Spike Lee and Cube’s own collaborator John Singleton. (Not to mention he beat out the brothers Hughes and Hudlin).

Another place where Rich was listed in impressive company was in Jonathan Demme’s best director Oscar acceptance speech for SILENCE OF THE LAMBS, in which he said, “About directing, I wanted very much to salute John Singleton and Matty Rich and Jodie Foster and Ernest Dickerson and a bunch of new people in the last year who have come on with very exciting, wonderful visions and really breathed tremendously important new life into our whole cinematic landscape.” According to a possibly self-written bio on sundance.org, “Mega Director Jonathan Demme discovered Matty Rich and STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN during an editing session for SILENCE OF THE LAMBS. He immediately took him under his wing and the movie went on to be a huge success winning the Sundance Film Festival’s Grand Jury Prize Award.”

But I think the fact that there’s currently only one external review link for this on IMDb (soon to be joined by mine) shows you how little it has been discussed in recent decades.

There were rumors that Spike Lee threatened Rich not to release STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN against JUNGLE FEVER, which both directors denied. Years later, in his own interview with BlackFilm, Lee called Rich “Matty Poor” and said, “It’s unfortunate because when he came out he got bad advice. He was like, ‘I’ve never read a film book, I don’t go to movies, I don’t know how to use a camera, I’m from the streets!’ And eventually that was reflected in his filmmaking. He knew nothing about film.”

To date Rich’s only other feature is 1994’s THE INKWELL, a ‘70s set Touchstone Pictures production with a heavy duty cast (Larenz Tate, Morris Chestnut, Joe Morton, Jada Pinkett Smith) that got poor reviews, though some now call it a cult classic. Rich continued to develop movies and TV shows that didn’t come to fruition – he wrote an unmade HBO biopic of Tupac Shakur and rewrote a Showtime movie called SUBWAY SCHOLAR that was to star Pam Grier and be produced by Whitney Houston.

In 2005 Rich finally re-emerged not with a new movie, but a video game, directing cut scenes for the UbiSoft “vehicular combat racing game” 187 Ride or Die. It takes place in South Central Los Angeles, more of a car-oriented place than where Rich grew up, and reunites the director with his INKWELL star Larenz Tate. GameSpot called it “an attempt at making a gangstered-up version of a Mario Kart game” and “a fairly standard car combat game with extremely repetitive gameplay and a hip-hop theme that feels about as fake and forced as possible.” GameSpy said that “the plot is fairly well done” but that its “ridiculous abuse of profanity and slang makes the game feel like a parody of the culture it’s trying to emulate.”

But the experience led Rich to a new industry. In a 2011 interview with Black Enterprise he talked about being CEO of Matty Rich Games, which he said would become “the leading mobile gaming company and publisher that will create Christian-themed and family fun games for African American consumers,” and Shadow and Act reported that he was hoping the mobile games he was developing could also be adapted into movies. I couldn’t find anything about how the games went, and definitely none of them became movies. But in 2016 he did return to filmmaking with a “faith-based supernatural thriller” short called C+U+R+E, intended as a teaser for a TV series.

Also in 2016 he co-wrote (with Andrea Williams) BEV: A Novel, a fictionalized account of Bev Luther, a white social worker who became a civil rights activist. But he still hasn’t made his third movie. In 2019 the Hollywood Reporter Hollywood reported that Rich would write and direct a thriller called CALLER 100, “which centers on a popular radio personality whose chance encounter with a female listener turns his life upside down.” But the film was to star and be produced by T.I., who has since been accused (along with his wife) of drugging and raping by more than 30 women.

Most of the people behind or in front of the camera on STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN did not go on to long movie careers. Editor Jack Haigis (who had done two previous movies) did follow this up with the well-received JUST ANOTHER GIRL ON THE I.R.T., and continued to work in indies up through the twenty-teens.

First timer George T. Odom (Ray) did continue in the business – his next role was as a barber in MALCOLM X, then he was in WHO’S THE MAN?, THE HURRICANE and various Law & Orders. But by far the most prolific career launched by STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN was Lawrence Gilliard Jr. (Dennis), credited as “Larry Gilliard Jr.” in his first role. His performance as Dennis is the highlight of STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN, and he soon followed it with a bunch of TV movies, an episode of Homicide: Life On the Street, and a co-starring role in George Foreman’s sitcom George. Then he started dividing his time between urban crime movies (MONEY TRAIN, THE SUBSTITUTE 2, ONE TOUGH COP, GANGS OF NEW YORK) and indies (LOTTO LAND, TREES LOUNGE, NEXT STOP WONDERLAND, CECIL B. DEMENTED) before landing his best known role on The Wire.

Back in the day I actually had a poster of STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN on my wall – not because it was my favorite, but because I liked it enough to take the poster when I saw it in the free bin at the video store. But I didn’t remember the movie well, so I was surprised when I looked at the cover again a few years ago, after becoming familiar with Gilliard from The Wire and The Walking Dead. I didn’t realize I’d had D’Angelo Barksdale on my wall in the ‘90s.

June 15th, 2021 at 8:16 am

Man I can’t believe Lee called him Matty Poor! Probably shouldn’t encourage such behaviour, but I have a weakness for incredibly petty\feeble disses like that