CANDYMAN (2021) is the first sequel in 22 years to CANDYMAN (1992), my pick for the best horror movie of the ‘90s. Though I don’t think this one’s nearly as good as Bernard Rose’s original, it’s much more worthy of the mantle than the previous sequels, Bill Condon’s New Orleans-set CANDYMAN: FAREWELL TO THE FLESH (1995) and (it goes without saying) Turi Meyer’s horrendous DTV CANDYMAN 3: DAY OF THE DEAD (1999). It’s nice that various trends have aligned to allow revisiting the subject decades later, minus any mercenary needs to strike while the iron is hot, and with the now-gentrified Chicago neighborhood where the first film took place providing a new angle from which to explore its still-relevant race and class themes. That seems to be the main point of interest for director Nia DaCosta (who did the excellent 2018 drama-with-some-crime LITTLE WOODS) and her producer/co-writers Jordan Peele (GET OUT, US) and Win Rosenfeld (executive producer of BLACKkKLANSMAN).

CANDYMAN (2021) is the first sequel in 22 years to CANDYMAN (1992), my pick for the best horror movie of the ‘90s. Though I don’t think this one’s nearly as good as Bernard Rose’s original, it’s much more worthy of the mantle than the previous sequels, Bill Condon’s New Orleans-set CANDYMAN: FAREWELL TO THE FLESH (1995) and (it goes without saying) Turi Meyer’s horrendous DTV CANDYMAN 3: DAY OF THE DEAD (1999). It’s nice that various trends have aligned to allow revisiting the subject decades later, minus any mercenary needs to strike while the iron is hot, and with the now-gentrified Chicago neighborhood where the first film took place providing a new angle from which to explore its still-relevant race and class themes. That seems to be the main point of interest for director Nia DaCosta (who did the excellent 2018 drama-with-some-crime LITTLE WOODS) and her producer/co-writers Jordan Peele (GET OUT, US) and Win Rosenfeld (executive producer of BLACKkKLANSMAN).

When the movie starts, the Universal logo comes on, so that globe spins around, and the letters come out, and then you realize they’re backwards. For half a second I thought something was wrong with the projection, but of course it’s referencing the importance of mirrors in the CANDYMAN films (where the titular restless spirit is summoned by chanting his name, like Bloody Mary). A couple of production company logos proceed to play backwards as well, so by the time the film proper started I had to look around until I spotted some numbers on a building and could finally be sure the movie was playing properly. Beginning the movie already off balance. Nice touch.

Then the opening credits are, in a sense, a mirror image of those in Rose’s film, which played over a perfect God’s eye view of early ‘90s Chicago, hovering over buildings, the camera and lettering following along the highway we’ll later be told was built to divide the city racially and economically. In DaCosta’s film the camera is on the ground looking up, as if to say that this will be CANDYMAN from a different perspective. And it is, in the sense that it’s told by a Black director and mostly Black writers, who are American, of the generation that grew up on the original film, and the story is centering on Black characters who live in the neighborhood, instead of a white graduate student (Virginia Madsen as Helen Lyle) coming there to research her thesis. But in a class sense it’s not entirely different – the last high-rises of Cabrini-Green, the real-life housing project where CANDYMAN was set and partially filmed, were demolished in 2011. In the sequel it’s now a hip arts neighborhood where the protagonists have just moved into a condo even nicer than what privileged Helen had on the other side of the highway.

I believe it’s implied that once-rising, now-stumbling artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, The Get Down, AQUAMAN, Watchmen) couldn’t afford it on his own. Some seem to think he’s a sponge on his girlfriend Brianna (Teyonah Parris, CHI-RAQ, IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK, POINT BLANK) and her money, which may or may not come from her job as a gallery director. After hearing about Helen Lyle from Brianna’s comic relief brother Troy (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett, DOM HEMINGWAY), Anthony gets interested in the history of his new neighborhood, wanders the less-re-developed areas for inspiration, and meets lifelong resident William Burke (Colman Domingo, TRUE CRIME, RED HOOK SUMMER, WITHOUT REMORSE), who tells him about Candyman. That becomes his new subject and obsession, and (in the tradition of Freddy Krueger) reminding people to be afraid of the hook-handed, bee-covered ghost of a lynching victim who comes out of your mirror brings him back. Anthony begins to fall apart mentally and even physically (an infected bee sting leads to some legitimately disgusting body horror) as people get murdered around him and his career only seems to benefit from it.

I believe it’s implied that once-rising, now-stumbling artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, The Get Down, AQUAMAN, Watchmen) couldn’t afford it on his own. Some seem to think he’s a sponge on his girlfriend Brianna (Teyonah Parris, CHI-RAQ, IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK, POINT BLANK) and her money, which may or may not come from her job as a gallery director. After hearing about Helen Lyle from Brianna’s comic relief brother Troy (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett, DOM HEMINGWAY), Anthony gets interested in the history of his new neighborhood, wanders the less-re-developed areas for inspiration, and meets lifelong resident William Burke (Colman Domingo, TRUE CRIME, RED HOOK SUMMER, WITHOUT REMORSE), who tells him about Candyman. That becomes his new subject and obsession, and (in the tradition of Freddy Krueger) reminding people to be afraid of the hook-handed, bee-covered ghost of a lynching victim who comes out of your mirror brings him back. Anthony begins to fall apart mentally and even physically (an infected bee sting leads to some legitimately disgusting body horror) as people get murdered around him and his career only seems to benefit from it.

This is very much a sequel, but it’s designed to make sense on its own. Tony Todd’s Candyman (a.k.a. Daniel Robitaille since part 2) is powered by his story being told, and sure enough the relevant facts are exposited FRIDAY THE 13TH PART 2 style, as scary stories (but with the addition of cool shadow puppets). In some ways the story may work better for newbies – a major connection to Rose’s film is not at all hidden if you’ve seen it, but plays as a big reveal when the characters discover it. And some of those in the Candyfan/Name of the Rose community seem to get confused by DaCosta’s introduction of Sherman Fields (Michael Hargrove, THE EXPRESS), the fur-collared, candy-giving, hook-handed, mirror-summoned spirit of a man killed in Cabrini-Green in the 1970s.

Sherman is not a rebooted Candyman – he’s part of the movie’s mythological expansion of Candyman as not one person, but a series of echoing atrocities, from the Reconstruction era to today, from lynch mobs to official police squads judging Black men as a threat and swarming on them. The first film is about long-past racist murders and archaic prejudices and taboos forever haunting a society with its literal and figurative architecture intentionally built to maintain those evils. It’s also about urban legends – Candyman had to keep his story alive by shedding enough “innocent blood” to ensure word of mouth. Helen and Daniel are discussed in this movie much more than they’re seen or heard, but as Candyman once said, “It is a blessed condition to be whispered of on street corners, to live in other people’s dreams, but not to have to be.”

In DaCosta’s film the line from Candyman’s backstory to modern police killings is drawn much more explicitly than in Rose’s, but maybe it has to be when told from a Black perspective. In a recording from her research project, Helen laments Cabrini residents not wanting to call police about anything, which I believe she interprets as a “stop snitching” code. But we see in flashbacks how William’s entire life is ruined by accidentally bringing neighborhood weirdo Sherman to the attention of the police – not even calling them on him – leading to the death of this innocent man. In the first film Helen recognized her white privilege in the way the police responded to her being assaulted in Cabrini-Green as opposed to two Black women being murdered there. But (at least before they decided she was a murderer and turned on her) she could count on their help and protection. Anthony, before being in any kind of trouble at all, instinctively ducks behind a building as a police car drives past.

Unlike Helen, he has to go through life knowing he could get Candyman-ed. He even has the same occupation as the first Candyman. Robitaille was a portrait artist for rich people, mostly white (information repeated in the new movie). Anthony is a different type of artist, attempting to channel his own emotions and socio-political statements into paintings and installations. But his work is at the mercy of curators and critics, some of whom seem full of shit, all of whom only take him seriously after his name and work become connected to a gruesome murder. Innocent blood is sustaining his career just as it sustains Candyman. When his name and the title of his installation are inexplicably mentioned on the news report about a murder he’s excited and says it’s “kind of cool” before awkwardly back-peddling. Like Candyman, he wants people to say his name.

But when he starts seeing a Candyman in reflections instead of himself, it has a double meaning. It’s the usual horror movie “oh my god, what am I becoming?”/“is this the dark side of me I try to deny?” type tropes, but also it’s “That could’ve easily been me” – a victim of police brutality and systemic racism. Especially a tall, muscular Black man like him. He could easily be the guy cops decide is threatening them.

Rose’s Candyman was a ghost haunting Cabrini-Green because it was the site of his murder. He represented the enduring damage of our racist history, so he mostly didn’t kill people who “deserve” it. I think that’s horror, that’s scary, but I understand this film’s desire to reshape him from a curse on this once-impoverished community to an avenger. Even pre-Candyman-obsession, Anthony’s art centers around lynchings of Black men, and I think we’re supposed to be uncomfortable with him commodifying Black death for trendy art people, many of them white. I think DaCosta is conscious of not wanting to do the same. Her Candyman’s innocent victims are mostly pretentious dicks, and mostly white. The least deserving are the group of teenage girls who summon him in a school restroom. They’re a diverse enough lineup to model for a catalog, but the one Black girl survives, witnessing it from inside a stall.

(Not important but I want to note that this scene features a Naked Ray Gun t-shirt and a Bad Brains patch.)

Before seeing the movie I noticed how many headlines and tweets called it “overstuffed” or similar. I didn’t really get that feeling, but the one thing I felt they could be referring to is the little bit we learn about Brianna’s dad being an artist and her witnessing his suicide. It comes up in a couple short flashbacks and vague conversations but, unless I’m missing something, doesn’t have a direct connection to Candyman, and she doesn’t find any closure about it. I like that, though. Here she is dealing with a fucked up boyfriend so similar to her fucked up dad and she doesn’t even have time to deal with her own issues because the supernatural stuff takes precedence. And because she always has to shoulder his shit anyway.

There’s plenty to nitpick about the movie. Both bad-guy-art critic Finley Stephens (Rebecca Spence, PUBLIC ENEMIES) and good guy curator Brianna are given pretentious art-talk lines that sound preposterous coming out of human mouths in conversation. William Burke having a life-ruining childhood experience while doing laundry and then growing up to own a laundromat comes across as pretty silly, even if it’s meant to be symbolic of him never moving beyond that incident. It seems like a bizarre oversight that Anthony doesn’t get blamed for murders he should be the instant prime suspect for, especially in a movie where the central theme is police blaming Black men for shit they didn’t do. And I think I need more viewings to decide whether or not I like the particular escalation of craziness that occurs at the climax.

But those things seem insignificant against its many strengths. Abdul-Mateen as Anthony and Parris as Brianna are the strong leads that FAREWELL TO THE FLESH lacked. The story organically connects to the original without copying its structure, and the setting and characters are related but very different. The major kill scenes are all staged in original and interesting ways – I especially like the massacre seen from inside the toilet stall, reflected in a makeup mirror dropped by one of the victims (which I’ll assume is an homage to that cool scene in the Jason Statham movie SAFE where a battle is seen from inside a car, in the side mirror). As a fan of the first film, I really appreciated that it found so many ways to connect to it without ever feeling like some “Here’s the part you fans were asking for!” bullshit. And I like that the contemporary horror trend it follows is the one most in line with the first film: to try to say something about race in the context of a good horror story. That wasn’t what you did back when part 3 came out.

When I wrote about the 1992 film in 2005 and even in 2015 it was my sense that it was largely just remembered as “that movie that freaked me out when I was a kid where you say Candyman five times in the mirror” and not recognized widely enough for the greatness of its filmmaking, much less what it was saying. But somewhere between GET OUT getting people interested in what Peele was calling “social horror,” the rebirth of Fangoria as more academic analysis of horror was becoming more popular on the internet, and the release of the documentary HORROR NOIRE: A HISTORY OF BLACK HORROR, it seemed like enough essays were being written about ol’ Beehive Ribs that I didn’t need to preach about him anymore. Everybody was on board again, it seemed like. But I’ve also been told that many (younger?) people find its racial politics offensive, and not in the “it’s teaching my kids critical race theory” sense. Supporting that claim is a recent Fangoria “Problematic Films” column titled “In Defense of Candyman.” It’s a good discussion, I recommend reading it, and it does in fact come out in favor of the film. But the part that makes me feel like I see very different things in CANDYMAN than other people do is when interviewee William O. Tyler says “had Virginia Madsen’s character just been cast with a Black actress” that “nothing about that character would change. There’s no reason why that character needs to be white.”

When I wrote about the 1992 film in 2005 and even in 2015 it was my sense that it was largely just remembered as “that movie that freaked me out when I was a kid where you say Candyman five times in the mirror” and not recognized widely enough for the greatness of its filmmaking, much less what it was saying. But somewhere between GET OUT getting people interested in what Peele was calling “social horror,” the rebirth of Fangoria as more academic analysis of horror was becoming more popular on the internet, and the release of the documentary HORROR NOIRE: A HISTORY OF BLACK HORROR, it seemed like enough essays were being written about ol’ Beehive Ribs that I didn’t need to preach about him anymore. Everybody was on board again, it seemed like. But I’ve also been told that many (younger?) people find its racial politics offensive, and not in the “it’s teaching my kids critical race theory” sense. Supporting that claim is a recent Fangoria “Problematic Films” column titled “In Defense of Candyman.” It’s a good discussion, I recommend reading it, and it does in fact come out in favor of the film. But the part that makes me feel like I see very different things in CANDYMAN than other people do is when interviewee William O. Tyler says “had Virginia Madsen’s character just been cast with a Black actress” that “nothing about that character would change. There’s no reason why that character needs to be white.”

I know it’s not up to me to judge what is “problematic” on this topic. I only ask to testify. As the likely greatest Black horror icon, Candyman belongs to the Black community in a very real way. And that’s why we hear this idea that the movie shouldn’t center on a white woman. Which is fine, but it’s really saying “I wish the character Candyman was in a movie other than CANDYMAN.” You’re asking for a totally different story, and I’m glad we get to see something like that in this sequel. But in the original telling, seeded in Clive Barker’s short story “The Forbidden” and expanded in Rose’s movie, it is, as they say, a feature and not a bug that Helen is an intruder in Cabrini-Green. Her friend Bernadette is Black and for class reasons doesn’t feel she belongs there either, but she has the sense to know she’s a tourist, a trespasser, and unwelcome. Helen, being a white person, does not get that at all. She’s all, Hello, I’m Very Important College Lady. Your daily struggles are perfect for my thesis. Can I come in?

You can’t take that out and say it’s the same thing. That’s what the movie’s about! That’s the point of the story!

As I wrote in 2005, when I was first realizing that the movie I thought was pretty good but not as good as NIGHTBREED when it came out was actually a masterpiece:

So Candyman haunts Cabrini Green, and race and class issues haunt the whole movie. The main character is some white lady (Virginia Madsen), who’s working on a thesis about urban legends when she hears the story of Candyman murdering somebody in Cabrini Green. She decides it will make her thesis more interesting to go find out about this murder. And the whole movie has the tension of the upper class white woman sticking her nose in other people’s business. It makes you uncomfortable to see her bothering (and in some cases endangering) the black cleaning staff at the college, some poor single mother in the projects, and a little kid. And it seems like they’re supposed to be impressed that she’s working on a thesis. Good job, white lady.

I was surprised at first to see Helen referred to as a “white savior” in the Fangoria column. Yeah, maybe she thinks she’s Michelle Pfeiffer in DANGEROUS MINDS, but she’s not helping anybody – she summons Candyman and drags poor Anne-Marie and her baby (and dog) into it. And Anne-Marie fucking warned her not to. “Whites never come here except to cause us a problem,” and that she did! So when Helen ends up saving the baby at the end she’s not so much a savior as someone taking responsibility for her own disastrous choices. And the fact that she replaces Candyman as the scary monster at the end is what sticks with me. Sandra Bullock never did that. But since Helen does sacrifice herself and the residents posthumously honor her for it, I can see how you could consider it to fit the trope. That’s fair.

Rose is obviously an outsider to the Black community of Chicago, and surely that leads to some blindspots. But he’s also an outsider to America itself, and I really believe that distance helped him recognize how to create a truly American horror icon like Candyman – a character rooted in American history but speaking to the present – while many over here were obsessing over European vampires in castles and shit.

But it is good and right that the CANDYMAN series has ended up in the hands of primarily Black filmmakers and characters. I’m glad that DaCosta was able to add a new chapter, and will be interested to see if another Black director brings us another one. More than that I hope that despite the dominance of so-called i.p. she and others will find opportunities to introduce us to new horror characters and ideas – whether about these types of issues or not about them at all – without the baggage of having to be so directly tied to the great works of others, the artifacts of the past, and the scary places we’ve already been to.

Candynerd shit:

I was glad Bernadette got a name drop.

I like that Troy tells Helen’s story as the crazy white lady who killed a dog, kidnapped a baby and got lit on fire, because that was the legend Candyman wanted to create.

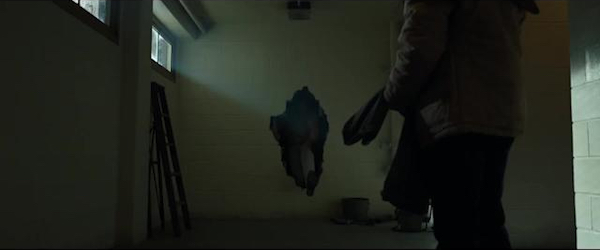

I thought it would be really cool if the hole in the wall Sherman hid in was supposed to be the same hole that had the Candyman face painted over it in the original film, as if different Candymen are inevitably drawn to that place. The shape is pretty similar but the room seems smaller, so it’s probly supposed to be an allusion to the earlier scene and not literally the same location. Maybe I’ll just take it as the latter anyway, because I like that idea.

Joke spoiler: I love that part where she takes a long look into the scary dark stairway behind the door in the back room at the laundromat and then literally says “Nope!” and closes the door. It’s funny to have a big laugh like that so late in a movie that really doesn’t have many jokes.

Further reading:

I want to recommend two really great pieces by people who straight up hated this sequel. Angelica Jade Bastien eviscerated it for Vulture, calling it “the most disappointing film of the year so far, limning not only the artistic failures of the individuals who ushered it to life, but the artistic failures of an entire industry that seeks to commodify Blackness to embolden its bottom line.” I really don’t get why she hates DaCosta’s direction and Abdul-Mateen and Parris’s performances so much (she also mentions that she’s “cool on” Peele as a director, for what that’s worth), but I can’t deny some of what she says about the muddled politics or how it compares to the original, and she made me consider many things I hadn’t.

I also have some pretty big disagreements with this review by Walter Chaw. I do not think this sequel is “hot garbage,” I think he’s crazy to describe the weird score by experimental musician Robert A.A. Lowe as “the standard notes and electronic fuzz,” even if it’s no Philip Glass, and his complaint about the laundromat pen ignores that she’s not, like, following an address on a random matchbook – seeing the pen reminds her of something weird Anthony said earlier about talking to the guy from the laundromat. Nevertheless I think this is a really great essay, particularly in regards to Barker’s short story and Rose’s movie, but it also makes plenty of criticisms worth considering. And I’m glad I’m not the only one calling it CANDYMAN 4.

Further viewing:

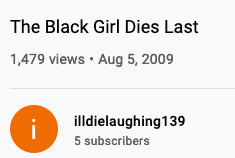

I found this ridiculous home video on Youtube with less than 1500 views in the 12 years since it was posted, where a teenage DaCosta and friends goof on slasher movies. The page says, “If you stumble upon this and you aren’t in this vid or know anyone in it, this is not to be taken seriously, it was made late one night in high school. i swear I make better movies now :P”

I can vouch for that! She definitely does!

P.S. I hope I live long enough to see SAMURAI MARATHON (2048), some young Japanese director’s sequel to Rose’s SAMURAI MARATHON (2019).

September 2nd, 2021 at 2:38 pm

Oh man, I’m glad I wasn’t the only one to think there was something wrong with the projection when those titles came up backwards! I had the exact same experience.

The “Nope!” line would have been funnier for me if someone in the theater hadn’t already literally shouted the same thing when the one girl runs out of the bathroom.